Alsace Censuses (1836-1866): A Valuable Tool for Genealogists

The censuses conducted in the Bas-Rhin between 1836 and 1866 are an invaluable source of information for anyone tracing their ancestry. Far more than just population counts, these documents provide a wealth of details about the daily and family life of past inhabitants. Below is a summary of their methodology, practical insights they offer, and concrete examples that can aid genealogical research.

A Rigorous and Contextualized Organization.

Starting in 1836, censuses in the Bas-Rhin were conducted following strict national directives. Each prefect was responsible for distributing standardized tables to local town halls to ensure uniform data collection. The nominative lists were produced in duplicate—one copy kept in municipal archives and the other sent to the prefect—covering the entire department, although some years (notably 1841 and 1846) have gaps. Furthermore, while the 1819 census, initiated by the prefect, only recorded heads of families in about 45% of localities, it was from 1836 onwards that the documents became more detailed and standardized.

Individuals were not listed in alphabetical order. Instead, the lists followed a geographical sequence: in villages, census agents recorded residents in the main town first, then in the surrounding hamlets. In cities, the census was conducted district by district, street by street, and even building by building. In some cases, to avoid any hierarchy, districts were identified by colors. For instance, in Bischwiller, the blue and red districts were already distinguished in 1819, while towns like Molsheim, Haguenau, and Strasbourg adopted similar systems or a cantonal division (north, south, east, and west, intra- and extramural).

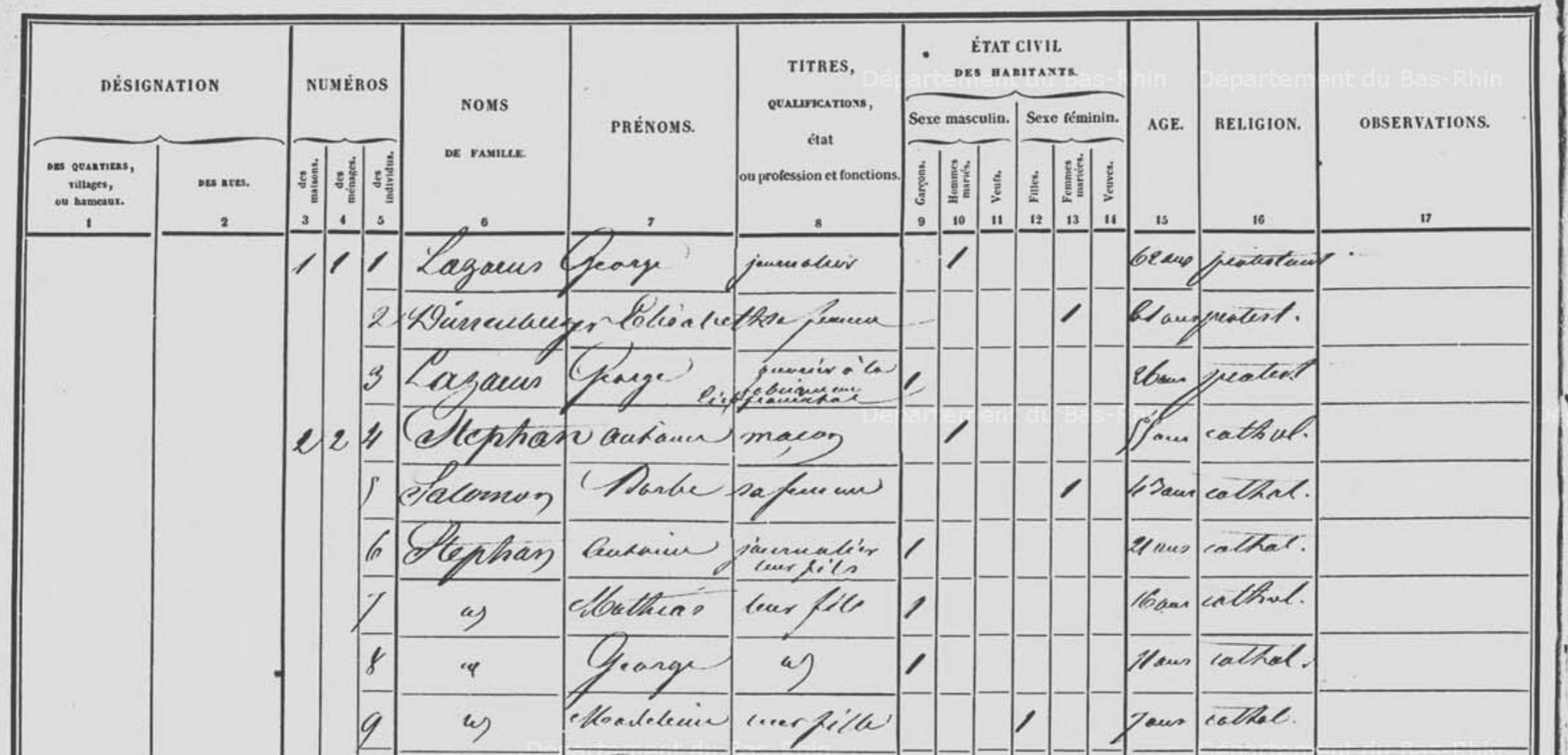

1846 census, Mitschdorf

Richly Detailed Information.

Beyond names and first names, these censuses provide a wealth of practical information, including:

• Identity and Family Composition:

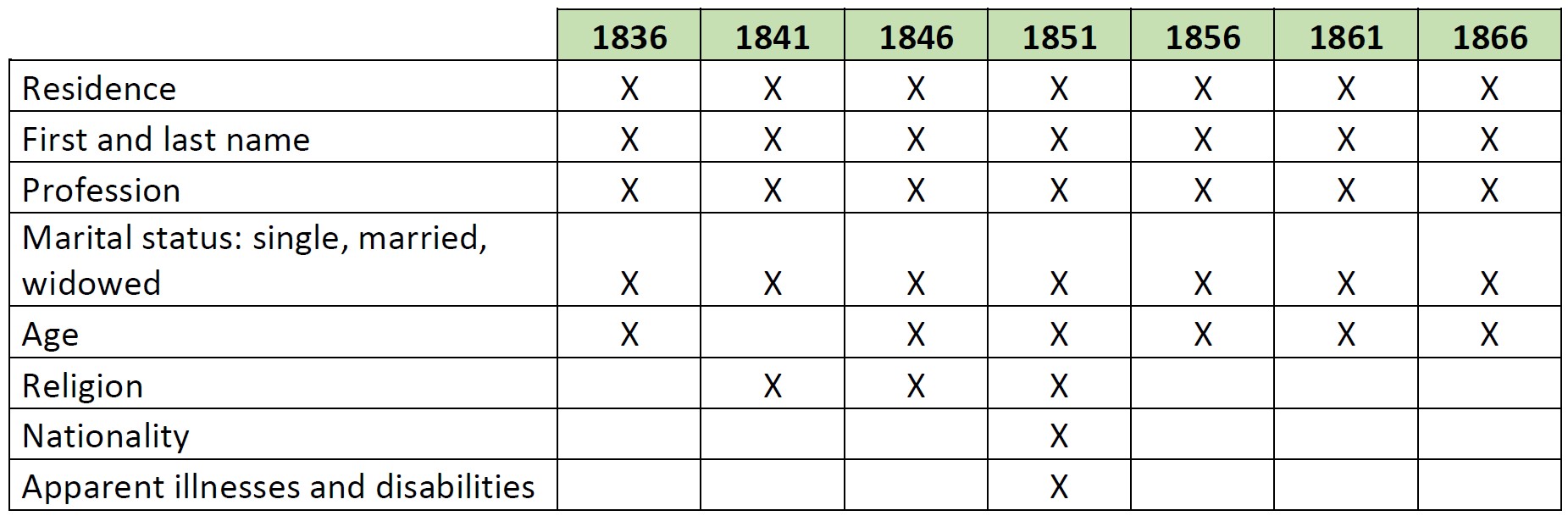

Each list (except for 1841) includes the age of individuals and their relationship to the head of the household. These details allow genealogists to reconstruct family structures and cross-reference them with other records such as birth and marriage certificates.

Additionally, censuses frequently show multiple generations living under the same roof. In many cases, one spouse’s parents resided with the family, reflecting a common intergenerational living arrangement of the time. In wealthier families, censuses also recorded domestic servants, listing their names and sometimes their roles, providing additional insight into the household’s social status.

• Religious Affiliation:

From 1851 onward, religion was systematically recorded in accordance with official instructions. However, in the Bas-Rhin, this information sometimes appeared as early as 1836 or consistently in certain localities (such as Kutzenhausen, except in 1856). Common abbreviations included “P” for Protestant, “C” for Catholic, “I” for Jewish (Israélite), and “A” for Anabaptist.

• Occupation and Social Status:

The census recorded each individual’s occupation, for example:

“Pierre Muller, 38 years old, farmer.”

This information helps genealogists understand a family’s economic and social standing.

• Additional Details:

Occasionally, extra annotations—such as notes on disabilities or individual characteristics—were included. These details help distinguish between individuals with the same name and add a personal dimension to genealogical research, making it easier to confirm family connections in a family tree.

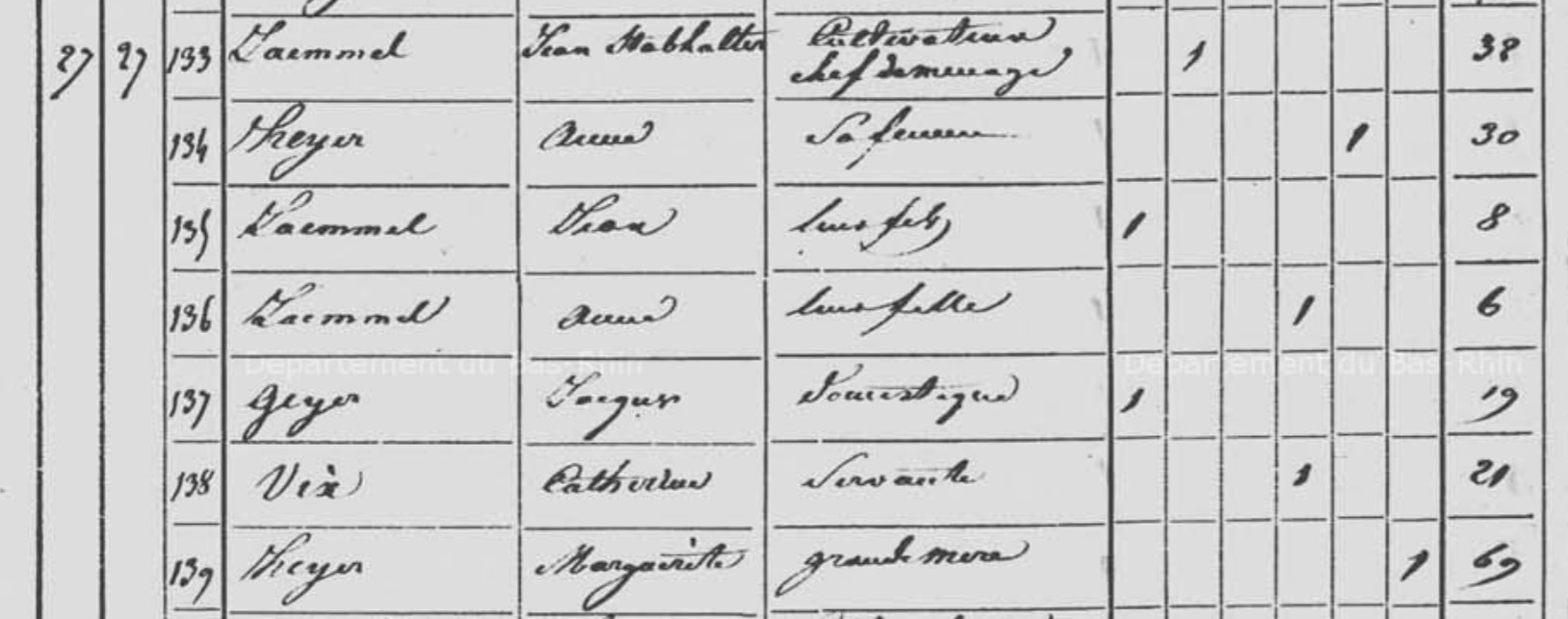

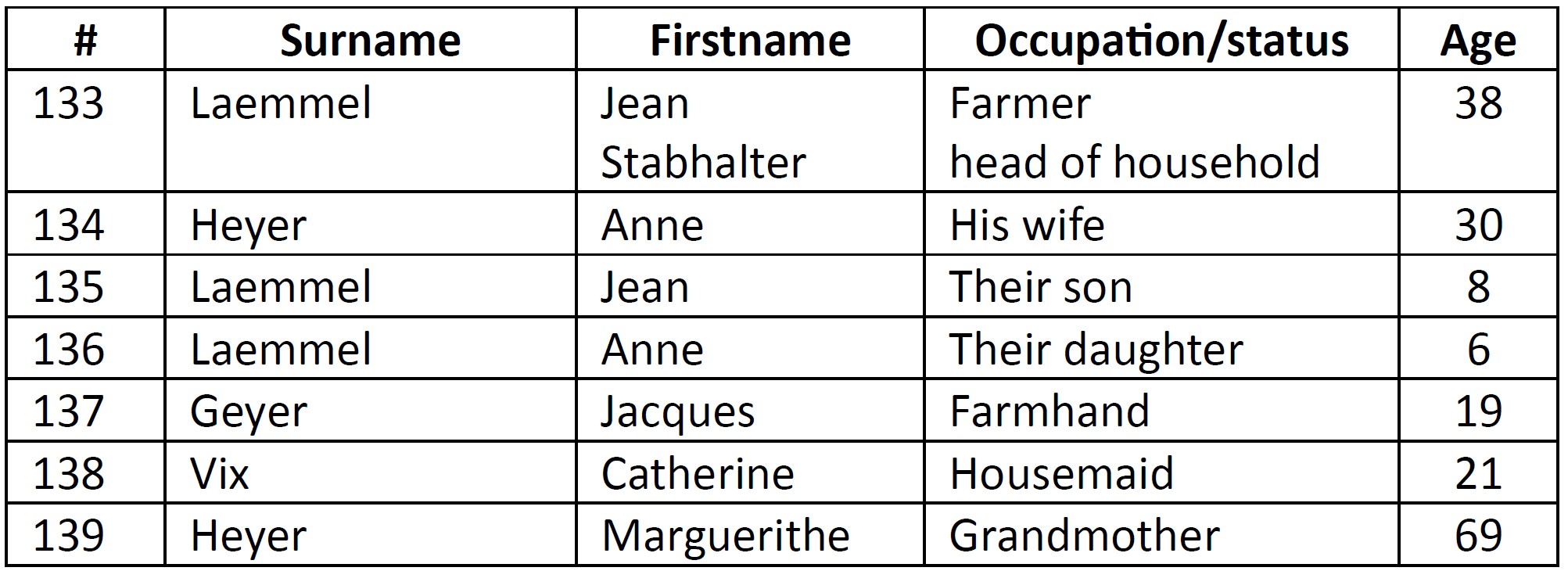

The image below illustrates the presentation of this information.:

1851 census, Melsheim, Archives d’Alsace, Strasbourg, 7M519

The table below summarizes the availability of various types of information in these censuses:

Richly Detailed Information.

It is important to note that while these censuses are rich in information, they also have limitations. For example, they do not allow researchers to pinpoint homes occupied before 1830, as this was around the time the first land registry (cadastre) was created. Additionally, while censuses list both homeowners and tenants, they do not specify whether an individual owned or rented their residence.

Nevertheless, by combining census data with other records (land registries, military documents, notarial deeds), researchers can enrich and validate their family trees while gaining a clearer understanding of the social and historical context in which their ancestors lived.

Nevertheless, by combining census data with other records (land registries, military documents, notarial deeds), researchers can enrich and validate their family trees while gaining a clearer understanding of the social and historical context in which their ancestors lived.

The Bas-Rhin censuses from 1836 to 1866 are far more than simple population counts. They offer a detailed snapshot of family, economic, and social life in the 19th century. For genealogists, these records are a valuable tool, providing practical insights into identity, family composition, occupations, religion, and even geographic details that help locate ancestral homes. By cross-referencing this information with other sources, researchers can reconstruct complex family histories and gain a deeper understanding of the social fabric of 19th-century Bas-Rhin.

Coming soon: the Haut-Rhin census of 1836-1866.

Sources:

– Listes nominatives de population du département du Bas-Rhin au XIXe siècle : contexte de production et données recueillies, Strasbourg, Archives départementales du Bas-Rhin. Éric Syssau, attaché de conservation du patrimoine.

– 1846 census, Mitschdorf, Archives d’Alsace, Strasbourg, 7M525.

– 1851 census, Melsheim, Archives d’Alsace, Strasbourg, 7M519.